In 1954, Hurricane Hazel swept through Toronto with unparalleled force. Although Toronto is no stranger to flooding—the first written account of a flood was in 1797—many were unprepared for the devastation this storm caused. Hurricane Hazel made its way to Ontario on October 15, 1954. Within 24 hours more than 200 millimetres of rainwater had fallen over the city. The Humber River and Etobicoke Creek watershed as well as Holland Marsh were the most affected bodies of water. These areas began to overflow and an excess of rainfall destroyed communities, roads, parks and public utilities. As a result of the storm, 81 people lost their lives and thousands were left homeless. It is estimated that a storm of this magnitude today would cause nearly $1 billion worth of damage.

Urban vs. Riverine Flooding

Urban areas are at risk of flooding because they are typically formed around lakes, rivers and harbours. Extreme weather conditions such as heavy rainfall, hurricanes, melting snow and ice are the most common causes of flooding in a city.

Urban Flooding:

Increased urbanization also contributes to flooding in cities. As a city develops, the ground gets covered in concrete, pavement and other materials that prevent rainwater from seeping into the soil and contribute to overflowing storm sewers. This is the kind of flooding that leads to wet basements and large puddles on roads. We can reduce urban flooding by creating more naturalized spaces like green roofs where rainwater can be absorbed instead of running into our storm sewers. As part of the Port Lands Flood Protection project, we are building green infrastructure into the streets to help manage stormwater on the new island, but the project won’t be able to prevent urban flooding in the surrounding areas.

Riverine Flooding:

When a lot of rain falls on a watershed, and the surrounding area is covered by pavement or other non-porous surfaces, a lot of that water ends up in local rivers. As the water in the river rises, the water overtops the normal banks of the river, creating dangerous floods that can wash away infrastructure and cause significant damage. The Port Lands Flood Protection project addresses this kind of flooding for a specific area of the Don River, where it meets the lake.

Flood Risk in the Port Lands

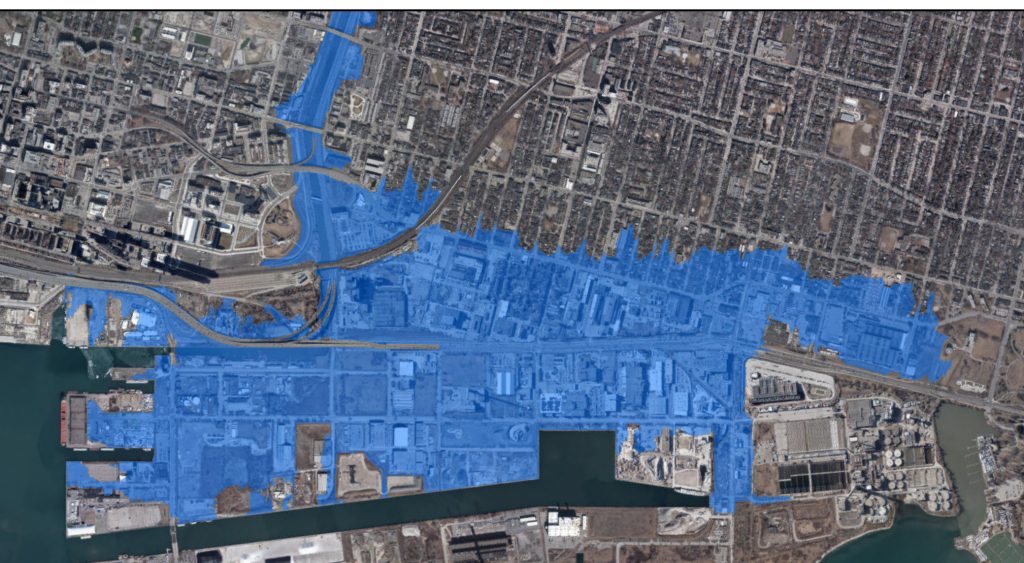

Toronto and Region Conservation (TRCA) has mapped out the areas in our city most vulnerable to flooding. Knowing which areas are at risk can help us determine where to build new homes and businesses. The parts of our city that were developed before the region’s floodplains were mapped out must find ways to lessen their chances of flooding. The Port Lands and surrounding communities is one such area. The Port Lands was created overtop of former wetlands. This was the natural mouth of the Don River. During a major storm, excessive water could safely flow into Lake Ontario. When the Port Lands were created in the mouth of the river, this natural greenspace was replaced by concrete. Now, during a major storm, this entire area could be overwhelmed with water that comes rushing down the river and overwhelms its capacity.

That’s why the Port Lands Flood Protection Project is so important: 290 hectares of Toronto’s southeastern downtown currently sit in the floodplain of the Don River.

Our design creates 100 per cent resiliency during a storm even larger than Hurricane Hazel. Water levels in Lake Ontario typically fluctuate by up to one metre above and below average lake levels. Because of this, we’re designing wetlands that can survive extremes of high or low water levels. The wetlands will be built at different elevations, which means if water levels go up or down, there will always be some areas available for fish, birds and other wildlife to find food and shelter. This keeps the entire system healthy.

Once flood protection is complete, a vast stretch of land within a 15-minute bike ride from central downtown will become a place where we can build new homes, public spaces and parkland, allowing the city to expand in a sustainable way.

What about the DVP?

The Port Lands Flood Protection project is designed to protect the Port Lands and portions of Leslieville and South Riverdale in a storm bigger than anything in recent memory. It is not designed to mitigate flooding on the Don Valley Parkway (DVP), which was built at a low point within the Don River flood plain.

This video shows how the flood modelling for a Hurricane Hazel-sized storm. The flooding that is addressed by the Port Lands Flood Protection project starts at around 0:14. The video shows how water would flood the DVP before spilling out into the flood plain in the Port Lands and surrounding areas. Once Port Lands Flood Protection is complete, the DVP would still be expected to flood, but the more widespread flooding in a more catastrophic storm would be controlled.

As this project has progressed, the assumptions underlying this model have changed slightly, and small details may have changed, however it is still a good general visualization of how the water in the Don River would act in a flood.

Do higher lake levels mean more flood risk in the Port Lands?

The Port Lands, in their existing condition, would be at risk from rising lake levels just like elsewhere on the waterfront – unrelated to its location in the Don River’s watershed. Our designs for infrastructure like dock walls and underground utilities take forecasted increased lake levels into account. Some adjustments have been made, and may continue to be made, to address possible future increases in the average high for lake levels. It’s important to note that higher lake levels would not result in catastrophic lake flooding on the future Villiers Island. That’s because as part of Port Lands Flood Protection, those areas will be raised well above high lake levels to address the flood risk from the Don River.

Key Benefits of Flood Protection

Our city stands to gain a brighter future once the Port Lands is flood protected.

In the event of a major flood, the measures put in place through this project will help prevent loss of life, and damages to businesses and homes. A healthier, more natural mouth for the Don River will revive the Don’s legacy as a hub for recreational activity. It will join Tommy Thompson Park as one of the best natural greenspaces in the city to explore, creating new opportunities to fish, hike and boat. An estimated 18,000 – 25,000 people will live in the Port Lands once it’s fully developed.

The project will also create jobs for an estimated 25,000-30,000 people living in Toronto. Another 50,000 people will work in the planned East Harbour development north of the Port Lands—an area that is also at risk of flooding. Overall, the project will contribute $4 billion to the Canadian economy.

Environmental Impact

Protecting the environment is also at the heart of this project. We are replacing industrial land in the Port Lands with 25 hectares of naturalized area—that includes new City parks and the naturalized wetlands within the river valley. Our work will strengthen biodiversity, help clean our waters and better connect us to the waterfront. The new river valley will create a new island, Ookwemin Minising, —Canada’s first climate positive community. This means it is designed to eliminate the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions it creates to below zero in an economically viable way. Climate positive developments accomplish this goal by reducing their own emissions and offsetting the emissions in neighbouring communities. The Island will showcase innovative products, policies, solutions and processes in economic sectors such as clean technology, design, sustainable construction and energy systems.