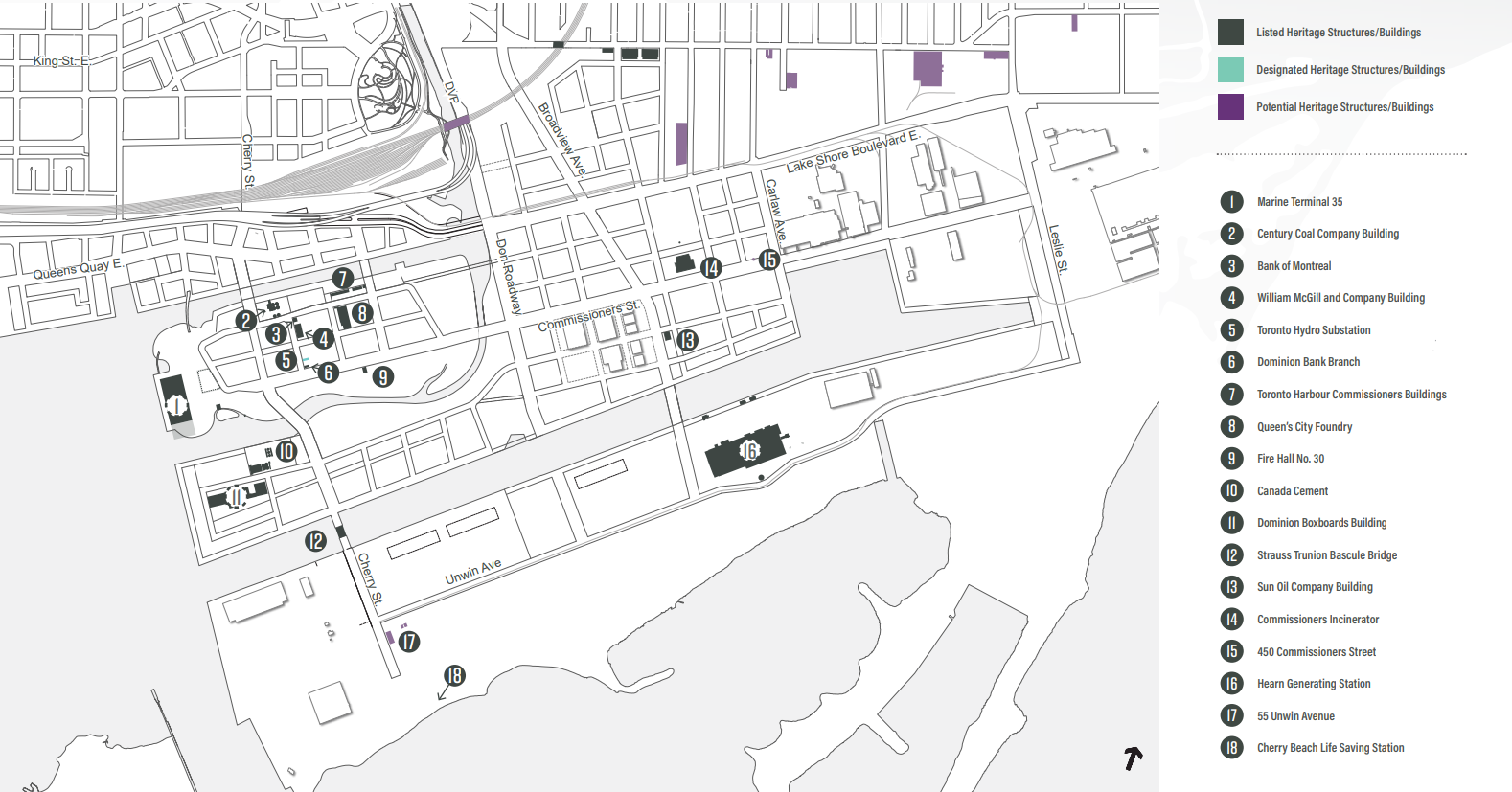

Planning for something new involves taking stock of what you’ve got and how it could be reused. The Port Lands has some surprising heritage assets – like the towering white crane that now sits in the future Promontory Park – and some striking buildings, along with industrial relics from silos to marine terminals.

The planning process documented these and assessed their cultural and heritage value in an evolving city.

Cherry Street’s heritage buildings

The Port Lands Planning Framework identifies Cherry Street as an important cultural corridor with its series of low-rise buildings that extend along the eastern edge between Villiers Street and Commissioners Street. The corridor is anchored at the northern end by the Bank of Montreal building at the corner of Villiers Street and Cherry Street and the Dominion Bank building at the southern end. Between these two anchors is the William McGill and Company Building and the Toronto Hydro Electrical building, designated under the Ontario Heritage Act in 2012.

All these buildings will remain, becoming part of the future community that will develop here once flood protection is complete. Learn more about the plans for ‘Villiers Island’ here.

Fire Hall No. 30 at the end of what’s currently called Munitions Street was relocated southward to accommodate a dedicated transit right-of-way on the recently rebuilt Commissioners Street. It will now be used as a pavilion at the entrance to the park lining the river valley south of Commissioners Street.

Watch us move the Fire Hall

Bridges

At the end of this Cherry Street Corridor sat one of two lift bridges in the area. The Cherry Street lift bridge over the Keating Channel is the smaller of two bascule lift bridges on Cherry Street. The second one crosses the Ship Channel, outside the boundaries for this project.

The bascule bridge over the Keating Channel was constructed in 1968 and includes an elevated bridge operator’s booth. This bridge replaced an earlier bascule bridge built in 1918 and an even-earlier rudimentary wooden drawbridge.

As part of the design for flood protection, a 2016 due diligence report found that this bridge and its footings would need to be removed. A Heritage Impact Assessment in 2019 didn’t recommend salvaging and refurbishing any part of the structure. But the plaque that was installed on the bridge foundations will be saved as part of plans to commemorate the bridge now that a new bridge crossing the Keating Channel has opened and the old bridge is being removed.

Old Cherry Street Bridge

A few days before it was slated to be removed, we got some questions about possibly saving the operator’s booth that sits atop the old bridge for reuse in the future. It can’t be left in place because it’s sitting on a section of the bridge that must be removed to achieve flood protection. Keeping the booth was never raised during consultation on detailed design, or in the City’s review of the Heritage Impact Assessment.

We thought: let’s investigate this. In the short time available to explore this possibility, we learned that the cost to safely remove and transport the booth would be high because it’s contaminated with hazardous materials like asbestos and lead. The equipment required for a salvage operation is also different from what we have available for removal. Because salvaging the booth was never contemplated, it would mean a delay to the construction schedule to change plans, get new crews and equipment and ensure the hazardous materials are safely managed. So, there is a cost that isn’t accounted for in the project budget due to: hazardous substance abatement, booth protection (during removal and while stored), alternative means and methods to safely and successfully dismantle and relocate the booth (in lieu of demolition and disposal), additional equipment requirements, storage site preparation, and construction fees due to delays. A delay of even a few weeks is particularly impactful because it would halt the dredging of the Keating Channel scheduled for April 2024. This dredging is part of the plan to ensure flood protection is completed on time. Because the activity is seasonal, a small delay would have a big impact on the overall schedule for achieving flood protection. Finally, we also couldn’t find a storage solution for the booth.

Read the Heritage Impact Assessment (2019) here.

Shipping in Toronto’s Port

Toronto has a hard working industrial port that will continue to operate as the area evolves and new communities develop.

Starting in the 1870s, industrialization began with the construction of breakwaters. Then came the Keating Channel and finally Ashbridge’s Bay Marsh was filled in, creating the Port Lands we know today.

After the St. Lawrence Seaway opened, renewed hope for Toronto’s burgeoning port and shipping industry led to the creation of Marine Terminal 35. Sitting at what is now a future park, the terminal began operation in 1959. The Port Lands Stakeholder Advisory Committee identified this structure as an important heritage asset to be conserved. Unfortunately, the building caught fire and we couldn’t preserve it. But the location and scale will be commemorated with a physical structure at that location.

Also preserved is the nearby Atlas Crane. A designated heritage structure, the crane is the last of its kind on the Great Lakes and was used to unload cargo at Marine Terminal 35, including Toronto icons like streetcars in 1966. The crane will be a showpiece along the shore of the new park where a series of new islands have been created for paddlers. To prepare it for life as a landmark, we have done some structural reinforcements and cladding around its base.

Learn more about the Port Lands: